- Home

- Jennifer Niven

All the Bright Places Page 19

All the Bright Places Read online

Page 19

At some point, I get up and go to the bathroom, mainly just to clear my head and text Violet, who comes home today. I sit waiting for her to text me back, flipping the faucets on and off. I wash my hands, wash my face, rummage through the cabinets. I am starting in on the shower rack when my phone buzzes. Home! Should I sneak over?

I write: Not yet. Am currently in hell, but will leave as soon as possible.

We go back and forth for a little while, and then I set off down the hallway, toward the noise and the people. I pass Josh Raymond’s room, and the door is ajar and he’s inside. I knock and he squeaks, “Come in.”

I go into what must be the largest room for a seven-year-old on the planet. The thing is so cavernous, I wonder if he needs a map, and it’s filled with every toy you can imagine, most requiring batteries.

I say, “This is quite a room you have, Josh Raymond.” I am trying not to let it bother me because jealousy is a mean, unpleasant feeling that only eats you from the inside, and I do not need to stand here, an almost-eighteen-year-old with a really sexy girlfriend, even if she’s not allowed to see me anymore, and worry about the fact that my stepbrother seems to own thousands of Legos.

“It’s okay.” He is sorting through a chest that contains—believe it or not—more toys, when I see them: two old-fashioned wooden stick horses, one black, one gray, that sit forgotten in a corner. These are my stick horses, the same ones I used to ride for hours when I was younger than Josh Raymond, pretending I was Clint Eastwood from one of the old movies my dad used to watch on our small, non-flat-screen TV. The one, incidentally, we still have and use.

“Those are pretty cool horses,” I say. Their names are Midnight and Scout.

He swivels his head around, blinks twice, and says, “They’re okay.”

“What are their names?”

“They don’t have names.”

I suddenly want to take the stick horses and march into the living room and whack my father over the head with them. Then I want to take them home with me. I’ll pay attention to them every day. I’ll ride them all over town.

“Where’d you get them?” I ask.

“My dad got them for me.”

I want to say, Not your dad. My dad. Let’s just get this straight right now. You already have a dad somewhere else, and even though mine isn’t all that great, he’s the only one I’ve got.

But then I look at this kid, at the thin face and the thin neck and the scrawny shoulders, and he’s seven and small for his age, and I remember what that was like. And I also remember what it was like growing up with my father.

I say, “You know, I had a couple of horses once, not as cool as these here, but they were still pretty tough. I named them Midnight and Scout.”

“Midnight and Scout?” He eyes the horses. “Those are good names.”

“If you want, you can have them.”

“Really?” He is looking up at me with owl eyes.

“Sure.”

Josh Raymond finds the toy he’s looking for—some sort of robocar—and as we walk out the door, he takes my hand.

Back in the living room, my father smiles his camera-ready SportsCenter smile and nods at me like we’re buddies. “You should bring your girlfriend over here.” He says this like nothing ever happened and he and I are the best of friends.

“That’s okay. She’s busy on Sundays.”

I can imagine the conversation between my father and Mr. Markey.

Your delinquent son has my daughter. At this moment, she is probably lying in a ditch thanks to him.

What did you think would happen? Damn right he’s a delinquent, and a criminal, and an emotional wreck, and a major-disappointment-weirdo-fuckup. Be grateful for your daughter, sir, because trust me, you would not want my son. No one does.

I can see Dad searching for something to say. “Well, any day is fine, isn’t it, Rosemarie? You just bring her by whenever you can.” He’s in one of his very best moods, and Rosemarie nods and beams. He slaps his hand against the chair arm. “Bring her over here, and we’ll put some steaks on the grill and something with beans and twigs on it for you.”

I am attempting not to explode all over the room. I am trying to keep myself very small and very contained. I am counting as fast as I can.

Thankfully, the game comes back on and he’s distracted. I sit another few minutes and then I thank Rosemarie for the meal, ask Kate if she can take Decca back to Mom’s, and tell everyone else I’ll see them at home.

I walk across town to my house, climb inside Little Bastard, and drive. No map, no purpose. I drive for what feels like hours, passing fields of white. I head north and then west and then south and then east, the car pushing ninety. By sunset, I’m on my way back to Bartlett, cutting through the heart of Indianapolis, smoking my fourth American Spirit cigarette in a row. I drive too fast, but it doesn’t feel fast enough. I suddenly hate Little Bastard for slowing me down when I need to go, go, go.

The nicotine scrapes at my throat, which is already raw, and I feel like throwing up, so I pull over onto the shoulder and walk around. I bend over, hands on my knees. I wait. When I don’t get sick, I look at the road stretched out ahead and start to run. I run like hell, leaving Little Bastard behind. I run so hard and fast, I feel like my lungs will explode, and then I go harder and faster. I’m daring my lungs and my legs to give out on me. I can’t remember if I locked the car, and God I hate my mind when it does that because now I can only think about the car door and that lock, and so I run harder. I don’t remember where my jacket is or if I even had one.

It will be all right.

I will be all right.

It won’t fall apart.

It will be all right.

It will be okay.

I’m okay. Okay. Okay.

Suddenly I’m surrounded by farms again. At some point, I pass a series of commercial greenhouses and nurseries. They won’t be open on Sunday, but I run up the drive of one that looks like a real mom-and-pop organization. A two-story white farmhouse sits on the back of the property.

The driveway is crowded with trucks and cars, and I can hear the laughter from inside. I wonder what would happen if I just walked in and sat down and made myself at home. I go up to the front door and knock. I am breathing hard, and I should have waited to knock so I could catch my breath, but No, I think, I’m in too much of a hurry. I knock again, louder this time.

A woman with white hair and the soft, round face of a dumpling answers, still laughing from the conversation she left. She squints at me through the screen, and then opens it because we’re in the country and this is Indiana and there is nothing to fear from our neighbors. It’s one of the things I like about living here, and I want to hug her for the warm but confused smile she wears as she tries to figure out if she’s seen me before.

“Hello there,” I say.

“Hello,” she says. I can imagine what I must look like, red face, no coat, sweating and panting and gasping for air.

I compose myself as fast as I can. “I’m sorry to disturb you, but I’m on my way home and I just happened to pass your nursery. I know you’re closed and you have company, but I wonder if I could pick out a few flowers for my girlfriend. It’s kind of an emergency.”

Her face wrinkles with concern. “An emergency? Oh dear.”

“Maybe that’s a strong word, and I’m sorry to alarm you. But winter is here, and I don’t know where I’ll be by spring. And she’s named for a flower, and her father hates me, and I want her to know that I’m thinking of her and that this isn’t a season of death but one for living.”

A man walks up behind her, napkin still tucked into his shirt. “There you are,” he says to the woman. “I wondered where you’d gone off to.” He nods at me.

She says, “This young man is having an emergency.”

I explain myself all over again to him. She looks at him and he looks at me, and then he calls to someone inside, telling them to stir the cider, and out he comes, napkin blo

wing a little in the cold wind, and I walk beside him, hands in my pockets, as we go to the nursery door and he pulls a janitor’s keychain off his belt.

I am talking a mile a minute, thanking him and telling him I’ll pay him double, and even offering to send a picture of Violet with the flowers—maybe violets—once I give them to her.

He lays a hand on my shoulder and says, “You don’t worry about that, son. I want you to take what you need.”

Inside, I breathe in the sweet, living scent of the flowers. I want to stay in here, where it’s warm and bright, surrounded by things that are living and not dead. I want to move in with this good-hearted couple and have them call me “son,” and Violet can live here too because there’s room enough for both of us.

He helps me choose the brightest blooms—not just violets, but daisies and roses and lilies and others I can’t remember the names of. Then he and his wife, whose name is Margaret Ann, wrap them in a refrigerated shipping bucket, which will keep the flowers hydrated. I try to pay them, but they wave my money away, and I promise to bring the bucket back as soon as I can.

By the time we’re done, their guests have gathered outside to see the boy who must have flowers to give to the girl he loves.

The man, whose name is Henry, drives me back to my car. For some reason, I expect it to take hours, but it only takes a few minutes to reach it. As we circle back around to the other side of the road, where Little Bastard sits looking patient and abandoned, he says, “Six miles. Son, you ran all that way?”

“Yes, sir. I guess I did. I’m sorry to pull you away from dinner.”

“That’s no worry, young man. No worry at all. Is something wrong with your car?”

“No, sir. It just didn’t go fast enough.”

He nods as if this makes all the sense in the world, which it probably doesn’t, and says, “You tell that girl of yours hello from us. But you drive back home, you hear?”

* * *

It’s after eleven when I reach her house, and I sit in Little Bastard for a while, the windows rolled down, the engine off, smoking my last cigarette because now that I’m here I don’t want to disturb her. The windows of the house are lit up, and I know she is in there with her parents who love her but hate me, and I don’t want to intrude.

But then she texts me, as if she knows where I am, and says, I’m glad to be back. When will I see you?

I text her: Come outside.

She is there in a minute, wearing monkey pajamas and Freud slippers, and a long purple robe, her hair pulled into a ponytail. I come up the walk carrying the refrigerated shipping bucket, and she says, “Finch, what on earth? Why do you smell like smoke?” She looks behind her, afraid they might see.

The night air is freezing, and a few flakes start to fall again. But I feel warm. She says, “You’re shivering.”

“Am I?” I don’t notice because I can’t feel anything.

“How long have you been out here?”

“I don’t know.” And suddenly I can’t remember.

“It snowed today. It’s snowing again.” Her eyes are red. She looks like she’s been crying, and this might be because she really hates winter or, more likely, because we’re coming up on the anniversary of the accident.

I hold out the bucket and say, “Which is why I wanted you to have these.”

“What is it?”

“Open and see.”

She sets down the bucket and undoes the latch. For a few seconds, all she does is breathe in the scent of the flowers, and then she turns to me and, without a word, kisses me. When she pulls away, she says, “No more winter at all. Finch, you brought me spring.”

For a long time, I sit in the car outside my house, afraid to break the spell. In here, the air is close and Violet is close. I’m wrapped up in the day. I love: the way her eyes spark when we’re talking or when she’s telling me something she wants me to know, the way she mouths the words to herself when she’s reading and concentrating, the way she looks at me as if there’s only me, as if she can see past the flesh and bone and bullshit right into the me that’s there, the one I don’t even see myself.

FINCH

Days 65 and 66

At school, I catch myself staring out the window and I think: How long was I doing that? I look around to see if anybody noticed, half expecting them to be staring at me, but no one is looking. This happens in every period, even gym.

In English, I open my book because the teacher is reading, and everyone else is reading along. Even though I hear the words, I forget them as soon as they’re said. I hear fragments of things but nothing whole.

Relax.

Breathe deeply.

Count.

After class, I head for the bell tower, not caring who sees me. The door to the stairs opens easily, and I wonder if Violet was here. Once I’m up and out in the fresh air, I open the book again. I read the same passage over and over, thinking maybe if I just get away by myself, I’ll be able to focus better, but the second I’m done with one line and move on to the next, I’ve forgotten the one that came before.

At lunch, I sit with Charlie, surrounded by people but alone. They are talking to me and around me, but I can’t hear them. I pretend to be interested in one of my books, but the words dance on the page, and so I tell my face to smile so that no one will see, and I smile and nod and I do a pretty good job of it, until Charlie says, “Man, what is wrong with you? You are seriously bringing me down.”

In U.S. Geography, Mr. Black stands at the board and reminds us once again that just because we’re seniors and this is our last semester, we do not need to slack off. As he talks, I write, but the same thing happens as when I was trying to read—the words are there one minute, and the next they’re gone. Violet sits beside me, and I catch her glancing at my paper, so I cover it up with my hand.

It’s hard to describe, but I imagine the way I am at this moment is a lot like getting sucked into a vortex. Everything dark and churning, but slow churning instead of fast, and this great weight pulling you down, like it’s attached to your feet even if you can’t see it. I think, This is what it must feel like to be trapped in quicksand.

Part of the writing is taking stock of everything in my life, like I’m running down a checklist: Amazing girlfriend—check. Decent friends—check. Roof over my head—check. Food in my mouth—check.

I will never be short and probably not bald, if my dad and grandfathers are any indication. On my good days, I can outthink most people. I’m decent on the guitar and I have a better-than-average voice. I can write songs. Ones that will change the world.

Everything seems to be in working order, but I go over the list again and again in case I’m forgetting something, making myself think beyond the big things in case there’s something hiding out behind the smaller details. On the big side, my family could be better, but I’m not the only kid who feels that way. At least they haven’t thrown me out on the street. School’s okay. I could study more, but I don’t really need to. The future is uncertain, but that can be a good thing.

On the smaller side, I like my eyes but hate my nose, but I don’t think my nose is what’s making me feel this way. My teeth are good. In general, I like my mouth, especially when it’s attached to Violet’s. My feet are too big, but at least they’re not too small. Otherwise I would be falling over all the time. I like my guitar, and my bed and my books, especially the cut-up ones.

I think through everything, but in the end the weight is heavier, as if it’s moving up the rest of my body and sucking me down.

The bell rings and I jump, which causes everyone to laugh except Violet, who is watching me carefully. I’m scheduled to see Embryo now, and I’m afraid he’ll notice something’s up. I walk Violet to class and hold her hand and kiss her and give her the best smile I can find so that she won’t watch me that way. And then, because her class is on the opposite side of school from the counseling office and I’m not exactly running to get there, I show up five minutes late to my

appointment.

Embryo wants to know what’s wrong and why I look like this, and does it have something to do with turning eighteen soon.

It’s not that, I tell him. After all, who wouldn’t want to be eighteen? Just ask my mom, who would give anything not to be forty-one.

“Then what is it? What’s going on with you, Finch?”

I need to give him something, so I tell him it’s my dad, which isn’t exactly a lie, more of a half-truth because it’s only one part of a much bigger picture. “He doesn’t want to be my dad,” I say, and Embryo listens so seriously and closely, his thick arms crossed over his thick chest, that I feel bad. So I tell him some more truth. “He wasn’t happy with the family he had, so he decided to trade us in for a new one he liked better. And he does like this one better. His new wife is pleasant and always smiling, and his new son who may or may not actually be related to him is small and easy and doesn’t take up much space. Hell, I like them better myself.”

I think I’ve said too much, but instead of telling me to man up and walk it off, Embryo says, “I thought your father died in a hunting accident.”

For a second, I can’t remember what he’s talking about. Then, too late, I start nodding. “That’s right. He did. I meant before he died.”

He is frowning at me, but instead of calling me a liar, he says, “I’m sorry you’ve had to deal with this in your life.”

I want to bawl, but I tell myself: Disguise the pain. Don’t call attention. Don’t be noticed. So with every last ounce of energy—energy that will cost me a week, maybe more—I say, “He does the best he can. I mean he did. When he was alive. The best sucks, but at the end of the day, it’s got more to do with him than me. And I mean, let’s face it, who couldn’t love me?”

As I sit across from him, telling my face to smile, my mind recites the suicide note of Vladimir Mayakovski, poet of the Russian Revolution, who shot himself at the age of thirty-six:

Ada Blackjack: A True Story of Survival in the Arctic

Ada Blackjack: A True Story of Survival in the Arctic The Aqua Net Diaries: Big Hair, Big Dreams, Small Town

The Aqua Net Diaries: Big Hair, Big Dreams, Small Town Holding Up the Universe

Holding Up the Universe American Blonde

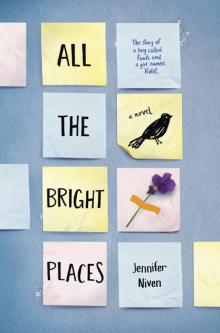

American Blonde All the Bright Places

All the Bright Places Velva Jean Learns to Fly

Velva Jean Learns to Fly The Ice Master

The Ice Master Breathless

Breathless The Aqua Net Diaries

The Aqua Net Diaries Becoming Clementine: A Novel

Becoming Clementine: A Novel