- Home

- Jennifer Niven

All the Bright Places Page 11

All the Bright Places Read online

Page 11

I shout over the noise, “I don’t like you either.” But he just laughs again.

FINCH

Day 15 (still)

On the way back to Violet’s house, I think up epitaphs for the people we know: Amanda Monk (I was as shallow as the dry creek bed that branches off the Whitewater River), Roamer (My plan was to be the biggest asshole I could be—and I was), Mr. Black (In my next life, I want to rest, avoid children, and be paid well).

So far she’s been quiet, but I know she’s listening, mostly because there’s no one else around but me. “What would yours say, Ultraviolet?”

“I’m not sure.” She tilts her head and gazes out over the dash at some distant point as if she’ll see the answer there. “What about yours?” Her voice sounds kind of drifting and far off, like she’s somewhere else.

I don’t even have to think about it. “Theodore Finch, in search of the Great Manifesto.”

She gives me a sharp look, and I can see she’s present and accounted for again. “I don’t know what that means.”

“It means ‘the urge to be, to count for something, and, if death must come, to die valiantly, with acclamation—in short, to remain a memory.’ ”

She goes quiet, as if she’s thinking this over. “So where were you Friday? Why didn’t you go to school?”

“I get these headaches sometimes. No big deal.” This isn’t an out-and-out lie, because the headaches are a part of it. It’s like my brain is firing so fast that it can’t keep up with itself. Words. Colors. Sounds. Sometimes everything else fades into the background and all I’m left with is sound. I can hear everything, but not just hear it—I can feel it too. But then it can come on all at once—the sounds turn into light, and the light goes too bright, and it’s like it’s slicing me in two, and then comes the headache. But it’s not just a headache I feel, I can see it, like it’s made up of a million colors, all of them blinding. When I tried to describe it to Kate once, she said, “You can thank Dad for that. Maybe if he hadn’t used your head as a punching bag.”

But that’s not it. I like to think that the colors and sounds and words have nothing to do with him, that they’re all me and my own brilliant, complicated, buzzing, humming, soaring roaring diving, godlike brain.

Violet says, “Are you okay now?” Her hair is windblown and her cheeks are flushed. Whether she likes it or not, she seems happy.

I take a good long look at her. I know life well enough to know you can’t count on things staying around or standing still, no matter how much you want them to. You can’t stop people from dying. You can’t stop them from going away. You can’t stop yourself from going away either. I know myself well enough to know that no one else can keep you awake or keep you from sleeping. That’s all on me too. But man, I like this girl.

“Yeah,” I say. “I think I am.”

At home, I access voicemail on the landline, the one Kate and I get around to checking when we remember, and there’s a message from Embryo. Shit. Shit. Shit. Shit. He called Friday because I missed our counseling session and he wants to know where in the hell I am, especially because he seems to have read the Bartlett Dirt, and he knows—or thinks he knows—what I was doing on that ledge. On the bright side, I passed the drug test. I delete the message and tell myself to be early on Monday, just to make it up to him.

And then I go up to my room, climb onto a chair, and contemplate the mechanics of hanging. The problem is that I’m too tall and the ceiling is too low. There’s always the basement, but no one ever goes down there, and it could be weeks, maybe even months, before Mom and my sisters would find me.

Interesting fact: Hanging is the most frequently used method of suicide in the United Kingdom because, researchers say, it’s viewed as being both quick and easy. But the length of the rope has to be calibrated in proportion to the weight of the person; otherwise there is nothing quick or easy about it. Additional interesting fact: The modern method of judicial hanging is termed the Long Drop.

That is exactly what it feels like to go to Sleep. It is a long drop from the Awake and can happen all at once. Everything just … stops.

But sometimes there are warnings. Sound, of course, and headaches, but I’ve also learned to look out for things like changes in space, as in the way you see it, the way it feels. School hallways are a challenge—too many people going too many directions, like a crowded intersection. The school gym is worse than that because you’re packed in and everyone is shouting, and you can become trapped.

I made the mistake of talking about it once. A few years ago, I asked my then good friend Gabe Romero if he could feel sound and see headaches, if the spaces around him ever grew or shrank, if he ever wondered what would happen if he jumped in front of a car or train or bus, if he thought that would be enough to make it stop. I asked him to try it with me, just to see, because I had this feeling, deep down, that I was make-believe, which meant invincible, and he went home and told his parents, and they told my teacher, who told the principal, who told my parents, who said to me, Is this true, Theodore? Are you telling stories to your friends? The next day it was all over school, and I was officially Theodore Freak. One year later, I grew out of my clothes because, it turns out, growing fourteen inches in a summer is easy. It’s growing out of a label that’s hard.

Which is why it pays to pretend you’re just like everyone else, even if you’ve always known you’re different. It’s your own fault, I told myself then—my fault I can’t be normal, my fault I can’t be like Roamer or Ryan or Charlie or the others. It’s your own fault, I tell myself now.

While I’m up on the chair, I try to imagine the Asleep is coming. When you’re infamous and invincible, it’s hard to picture being anything but awake, but I make myself concentrate because this is important—it’s life or death.

Smaller spaces are better, and my room is big. But maybe I can cut it in half by moving my bookcase and dresser. I pick up the rug and start pushing things into place. No one comes up to ask what the hell I’m doing, although I know my mom and Decca and Kate, if she’s home, must hear the pulling and scraping across the floor.

I wonder what would have to happen for them to come in here—a bomb blast? A nuclear explosion? I try to remember the last time any of them were in my room, and the only thing I can come up with is a time four years ago when I really did have the flu. Even then, Kate was the one who took care of me.

FINCH

Days 16 and 17

In order to make up for missing Friday, I decide to tell Embryo about Violet. I don’t mention her by name, but I’ve got to say something to someone other than Charlie or Brenda, who don’t do more than ask me if I’ve gotten laid yet or remind me of the ass-kicking Ryan Cross will give me if I ever make a move on her.

First, though, Embryo has to ask me if I’ve tried to hurt myself. We run through this routine every week, and it goes something like this:

Embryo: Have you tried to hurt yourself since I saw you last?

Me: No, sir.

Embryo: Have you thought about hurting yourself?

Me: No, sir.

I’ve learned the hard way that the best thing to do is say nothing about what you’re really thinking. If you say nothing, they’ll assume you’re thinking nothing, only what you let them see.

Embryo: Are you bullshitting me, son?

Me: Would I bullshit you, an authority figure?

Because he still hasn’t acquired a sense of humor, he squints at me and says, “I certainly hope not.”

Then he decides to break routine. “I know about the article in the Bartlett Dirt.”

I actually sit speechless for a few seconds. Finally I say, “You can’t always believe what you read, sir.” It comes out snarky. I decide to drop the sarcasm and try again. Maybe it’s because he’s thrown me. Or maybe it’s because he’s worried and he means well, and he is one of the few adults in my life who pay attention. “Really.” My voice actually cracks, making it clear to both of us that the stupid artic

le bothers me more than I let on.

After this exchange is over, I spend the rest of the time proving to him how much I have to live for. Today is the first day I’ve brought up Violet.

“So there’s this girl. Let’s call her Lizzy.” Elizabeth Meade is head of the macramé club. She’s so nice, I don’t think she’d mind if I borrowed her name in the interest of guarding my privacy. “She and I have gotten to be kind of friendly, and that’s making me very, very happy. Like stupidly happy. Like so-happy-my-friends-can’t-stand-to-be-around-me happy.”

He is studying me as if trying to figure out my angle. I go on about Lizzy and how happy we are, and how all I want to do is spend my days being happy about how happy I am, which is actually true, but finally he says, “Enough. I get it. Is this ‘Lizzy’ the girl from the paper?” He makes air quotes around her name. “The one who saved you from jumping off the ledge?”

“Possibly.” I wonder if he’d believe me if I told him it was the other way around.

“Just be careful.”

No, no, no, Embryo, I want to say. You, of all people, should know better than to say something like this when someone is so happy. “Just be careful” implies that there’s an end to it all, maybe in an hour, maybe in three years, but an end just the same. Would it kill him to be, like, I’m really glad for you, Theodore. Congratulations on finding someone who makes you feel so good?

“You know, you could just say congratulations and stop there.”

“Congratulations.” But it’s too late. He’s already put it out there and now my brain has grabbed onto “Just be careful” and won’t let go. I try to tell it he might have meant “Just be careful when you have sex. Use a condom,” but instead, because, you know, it’s a brain, and therefore has—is—a mind of its own, it starts thinking of every way in which Violet Markey might break my heart.

I pick at the arm of the chair where someone has sliced it in three places. I wonder who and how as I pick pick pick and try to silence my brain by thinking up Embryo’s epitaph. When this doesn’t work, I make up one for my mother (I was a wife and am still a mother, although don’t ask me where my children are) and my father (The only change I believe in is getting rid of your wife and children and starting over with someone else).

Embryo says, “Let’s talk about the SAT. You got a 2280.” He sounds so surprised and impressed, I want to say, Oh yeah? Screw you, Embryo.

The truth is, I test well. I always have. I say, “Congratulations would be appropriate here as well.”

He charges on ahead as if he hasn’t heard me. “Where are you planning on going to college?”

“I’m not sure yet.”

“Don’t you think it’s time to give some thought to the future?”

I do think about it. Like the fact that I’ll see Violet later today.

“I do think about it,” I say. “I’m thinking about it right now.”

He sighs and closes my file. “I’ll see you Friday. If you need anything, call me.”

Because BHS is a giant school with a giant population of students, I don’t see Violet as often as you might think. The only class we have together is U.S. Geography. I’m in the basement when she’s on the third floor, I’m in the gym when she’s all the way across the school in Orchestra Hall, I’m in the science wing when she’s in Spanish.

On Tuesday, I say to hell with it and meet her outside every one of her classes so I can walk her to the next. This sometimes means running from one end of the building to the other, but it’s worth every step. My legs are long, so I can cover a lot of ground, even if I have to dodge people left and right and sometimes leap over their heads. This is easy to do because they move in slow motion, like a herd of zombies or slugs.

“Hello, all of you!” I shout as I run. “It’s a beautiful day! A perfect day! A day of possibility!” They’re so listless, they barely look up to see me.

The first time I find Violet, she’s walking with her friend Shelby Padgett. The second time, she says, “Finch, again?” It’s hard to tell if she’s happy to see me or embarrassed, or a combination. The third time, she says, “Aren’t you going to be late?”

“What’s the worst they can do?” I grab her hand and drag her bumping along. “Coming through, people! Clear the way!” After seeing her to Russian literature, I jog back down the stairs and down more stairs and through the main hall, where I run directly into Principal Wertz, who wants to know what I think I’m doing out of class, young man, and why I’m running as if the enemy is on my heels.

“Just patrolling, sir. You can’t be too safe these days. I’m sure you’ve read about the security breaches over at Rushville and New Castle. Computer equipment stolen, library books destroyed, money taken from the front office, and all in the light of day, right under their noses.”

I’m making this up, but it’s clear he doesn’t know that. “Get to class,” he tells me. “And don’t let me catch you again. Do I need to remind you you’re on probation?”

“No, sir.” I make a show of walking calmly in the other direction, but when the next bell rings, I take off down the hall and up the stairs like I’m on fire.

The first people I see are Amanda, Roamer, and Ryan, and I make the mistake of accidentally ramming into Roamer, which sends him into Amanda. The contents of her purse go spiraling across the hallway floor, and she starts screaming. Before Ryan and Roamer can beat me to a six-foot-three-inch bloody pulp, I sprint away, putting as much distance between them and me as I can. I’ll pay for this later, but right now I don’t care.

This time Violet is waiting. As I double over, catching my breath, she says, “Why are you doing this?” And I can tell she isn’t happy or embarrassed, she’s pissed.

“Let’s run so you’re not late to class.”

“I’m not running anywhere.”

“I can’t help you then.”

“Oh my God. You are driving me crazy, Finch.”

I lean in, and she backs up into a locker. Her eyes are darting everywhere like she’s terrified someone might see Violet Markey and Theodore Finch together. God forbid Ryan Cross walks by and gets the wrong idea. I wonder what she’d say to him—It’s not what it looks like. Theodore Freak is harassing me. He won’t leave me alone.

“Glad I can return the favor.” Now I’m pissed. I rest one hand against the locker behind her. “You know, you’re a lot friendlier when we’re by ourselves and no one’s around to see us together.”

“Maybe if you didn’t run through the halls and shout at everyone. I can’t tell if you do all this because it’s expected or because it’s just the way you are.”

“What do you think?” My mouth is an inch from hers, and I wait for her to slap me or push me away, but then she closes her eyes, and that’s when I know—I’m in.

Okay, I think. Interesting turn of events. But before I can make a move, someone yanks me by the collar and jerks me back. Mr. Kappel, baseball coach, says, “Get to class, Finch. You too.” He nods at Violet. “And that’s detention for the both of you.”

After school, she walks into Mr. Stohler’s room and doesn’t even look at me. Mr. Stohler says, “I guess there really is a first time for everything. We’re honored to have your company, Miss Markey. To what do we owe the pleasure?”

“To him,” she says, nodding in my direction. She takes a seat at the front of the room, as far away from me as she can get.

VIOLET

142 days to go

Two a.m. Wednesday. My bedroom.

I wake up to the sound of rocks at my window. At first I think I’m dreaming, but then I hear it again. I get up and peek through the blinds, and Theodore Finch is standing in my front yard dressed in pajama bottoms and a dark hoodie.

I open the window and lean out. “Go away.” I’m still mad at him for getting me detention, first of my life. And I’m mad at Ryan for thinking we’re going out again, and whose fault is that? I’ve been acting like a tease, kissing him on his dimple, kissing him at the dri

ve-in. I’m mad at everyone, mostly myself. “Go away,” I say again.

“Please don’t make me climb this tree, because I’ll probably fall and break my neck and we have too much to do for me to be hospitalized.”

“We don’t have anything else to do. We’ve already done it.”

But I smooth my hair and roll on some lip gloss and pull on a bathrobe. If I don’t go down, who knows what might happen?

By the time I get outside, Finch is sitting on the front porch, leaning back against the railing. “I thought you’d never come,” he says.

I sit down beside him, and the step is cold through my layers. “Why are you here?”

“Were you awake?”

“No.”

“Sorry. But now that you are, let’s go.”

“I’m not going anywhere.”

He stands and starts walking to the car. He turns and says too loudly, “Come on.”

“I can’t just take off when I want to.”

“You’re not still mad, are you?”

“Actually, yes. But look at me. I’m not even dressed.”

“Fine. Leave the ugly bathrobe. Get some shoes and a jacket. Do not take time to change anything else. Write a note to your parents so they won’t worry if they wake up and find you gone. I’ll give you three minutes before I come up after you.”

We drive toward Bartlett’s downtown. The blocks are bricked off into what we call the Boardwalk. Ever since the new mall opened, there’s been no reason to come here except for the bakery, which has the best cupcakes for miles. The businesses here are hangers-on, relics from about twenty years ago—a sad and very old department store, a shoe store that smells like mothballs, a toy store, a candy shop, an ice cream parlor.

Ada Blackjack: A True Story of Survival in the Arctic

Ada Blackjack: A True Story of Survival in the Arctic The Aqua Net Diaries: Big Hair, Big Dreams, Small Town

The Aqua Net Diaries: Big Hair, Big Dreams, Small Town Holding Up the Universe

Holding Up the Universe American Blonde

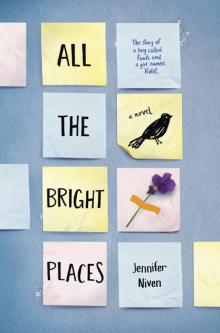

American Blonde All the Bright Places

All the Bright Places Velva Jean Learns to Fly

Velva Jean Learns to Fly The Ice Master

The Ice Master Breathless

Breathless The Aqua Net Diaries

The Aqua Net Diaries Becoming Clementine: A Novel

Becoming Clementine: A Novel